This post is a recent piece by Matthew Yglesias from his Substack site Slow Boring. Here’s a link to the original. It’s part of an ongoing series of posts here about the problems of meritocracy (for example, this, this, this, and this.)

As Yglesias notes, most critiques of meritocracy are focused on the failures of the system to be sufficiently meritocratic. The ideal of meritocracy is sullied, they say, because it fails to reward the people with the most merit, broadly defined. Instead, the process of merit-based selection rewards those who are best at gaming the system, whose prime skill is at acquiring the badges of merit without having to demonstrate substantive merit.

Yglesias flips this narrative on its head by stipulating that meritocracy is overall pretty good at identifying people who are really smart and then assigning them to positions of leadership. It’s not that having smarts isn’t useful for leaders. We don’t want incompetence at the highest levels, as we learned from the Trump administration, but smarts alone are not sufficient. What we need most is leaders with strong core values, people who honor the professional norms of the roles they occupy, as we also learned from observing Trump. Highly skilled technicians without honor are more effective at exploiting their roles than at performing them. Examples abound. What we need, he notes, is not the brightest but the best.

See what you think.

Meritocracy is Bad

America is good at elevating “the best” people; the problem is that’s a bad idea

Matthew Yglesias

Something I’ve often found is that arguments that start off promising to offer a critique of meritocracy end up, in fact, simply arguing that today’s existing society fails to live up to meritocratic ideas. So, I was excited when I recently read a Helen Andrews article arguing “our authors fail as critics of meritocracy because they cannot get their heads outside of it.”

That, I thought, is exactly what critics of meritocracy get wrong!

But then midway through the essay, I come to this part, where she does exactly the thing that I thought she was criticizing:

Here we have the meritocratic delusion most in need of smashing: the notion that the people who make up our elite are especially smart. They are not—and I do not mean that in the feel-good democratic sense that we are all smart in our own ways, the homely-wise farmer no less than the scholar. I mean that the majority of meritocrats are, on their own chosen scale of intelligence, pretty dumb.

So I want to actually make the argument that I merely thought Andrews was making.

The current system of social hierarchy in the United States is of course not a perfect meritocracy (nothing is ever perfect), but it’s genuinely pretty successful on its own meritocratic terms. The problem is that those terms are bad. American society will not get better if we try to make it more genuinely meritocratic along any dimension of possible understanding of what the term means. What we need to do is relax our level of ideological investment in the idea of meritocracy and be more chill.

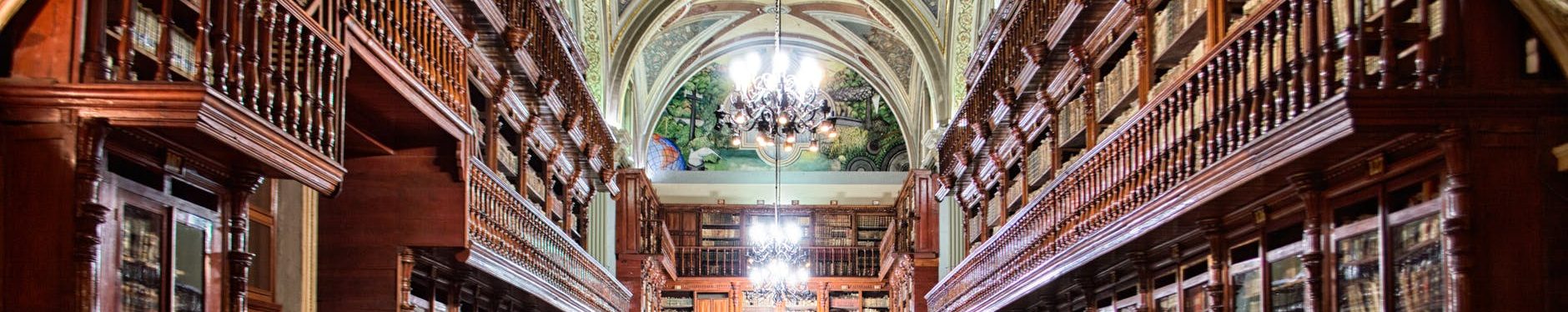

Our smart elites

(Photo by William Thomas Kane / Getty)

I think the idea that America’s existing elites are somehow “pretty dumb” is itself one of the dumbest lies that people tell themselves. I recently did a virtual event with some Yale students, and the questions were all really good and perceptive. Every time I’ve done an event with Yale students over the past 18 years of my career, the questions have all been really good. Harvard events also get great questions. I’ve also been to Penn twice — great questions. When I’ve been to flagship public university campuses in Ann Arbor and Austin it’s the same — really good.

I’m not quite sure how I’d compare the very best private schools to the very best public schools. A very large share of the smartest 18-year-olds in Michigan and Wisconsin and Texas enroll at their local state university, and that seems to me to just show good sense on their part.

But when you drop down an obvious rung or two on the prestige ladder, the quality of your campus event dips. The professors at the less-prestigious schools usually went to grad school at the more-prestigious schools, and they taught the more-prestigious undergrads as TAs before becoming professors at the less-prestigious schools. And if you ask them “how do the admissions departments do at sorting 18-year-olds by intelligence?” they will tell you that the admissions departments are pretty good at this! Yes, there are various compromises and departures from a pure meritocratic ideal. And there is inherent uncertainty involved in evaluating teenagers.

But they do it pretty well! The meritocracy works! There is a reason that in addition to various major cities, Google has offices in Ann Arbor and Madison. As Slow Boring readers know, we are in fact missing out on some smart kids (mostly ones living in low-income rural communities), but the fact is we are doing pretty good at sorting.

And if you talk to people with a curious and open mind, you’ll pretty quickly find out that New York Times reporters are really smart. So are McKinsey consultants. So are the people working at successful hedge funds. So are Ivy League professors. Probably the smartest person I know was in a great grad program in the humanities, couldn’t quite get a tenure track job because of timing and the generally lousing job market in academia, and wound up with a job in finance at a firm that is famous for hiring really smart people with unorthodox backgrounds. Our society is great at identifying smart people and giving them important or lucrative jobs.

This just turns out to be an outcome that still has some problems.

Smart people do bad things

If you want a story about the problem with meritocracy, I would read Dylan Scott’s recent article about what researchers have found about the consequences of private equity takeovers of nursing homes:

The researchers studied patients who stayed at a skilled nursing facility after an acute episode at a hospital, looking at deaths that fell within the 90-day period after they left the nursing home. They found that going to a private equity-owned nursing home increased mortality for patients by 10 percent against the overall average.

Or to put it another way: “This estimate implies about 20,150 Medicare lives lost due to [private equity] ownership of nursing homes during our sample period” of 12 years, the authors — Atul Gupta, Sabrina Howell, Constantine Yannelis, and Abhinav Gupta — wrote. That’s more than 1,000 deaths every year, on average.

Why do private equity takeovers kill so many people? It’s not because the Wall Street boys are dimwitted. The people who work in private equity are very smart. Their job is to look for companies that, for whatever reason, are not being managed in a way that maximizes shareholder value. Then they take them over with borrowed money and rejigger operations so as to increase profits. In the case of nursing homes, it turns out that basically, if you give patients more drugs, you can get away with lower staffing levels, and then you can drain the resources that are freed up by that in various ways:

The combination of fewer nurses and more antipsychotic drugs could explain a significant portion of the disconcerting mortality effect measured by the study. Private equity firms were also found to spend more money on things not related to patient care in order to make money — such as monitoring fees to medical alert companies owned by the same firm — which drains still more resources away from patients.

“These results, along with the decline in nurse availability, suggest a systematic shift in operating costs away from patient care,” the authors concluded.

There’s a lot more you could say about this story looking specifically at the lens of nursing home operations. But I’m interested in meritocracy. And the point here is that things can go awry not despite, but because smart people are in charge.

The healthcare sector poses these kinds of questions in droves. To become a medical doctor, you generally need to get into a good college, have decent grades there, get a good score on a pretty hard standardized test, and then put in a bunch of time into a challenging graduate education program. So doctors are quite a bit smarter than the average American, which seems reasonable. Nobody wants a dumb doctor. But you also don’t really want a shrewd doctor who is putting his smarts to use figuring out how to take advantage of his asymmetrical information vis-a-vis his patients to buy unnecessary services. You want healers who, yes, earn a comfortable living, but also comport themselves according to a code of honor and offer legitimate medical advice.

But this concept of honor and virtue is consistently at odds with the merit principle.

The honor code

I watched “The Queen’s Gambit” recently, which is a pretty great miniseries about a chess prodigy. Chess is an extremely meritocratic field, but there’s an important scene at the beginning of the game where Mr. Shaibel teaches our soon-to-be chess prodigy about sportsmanship.

This sets the tone in a lot of ways for the series, which features tons of high-stakes competitive chess but no cheating. There are a lot of Cold War undertones when, later in the series, Beth is the U.S. Champion and she goes to Moscow to take on the best Soviet players. But the Russians don’t try to poison her food or pump disturbing noises into her hotel room to stop her from sleeping. All the chess people in “The Queen’s Gambit” behave with a great deal of honor.

That’s the difference between Donald Trump and John McCain.

During the Vietnam War, McCain was a naval aviator who was shot down over enemy territory and held prisoner and tortured for years. Trump exploited loopholes in the Selective Service system to get a deferral due to supposed bone spurs. And throughout his business career, Trump succeeded with sharp practices. Liberals who’ve had their brains poisoned by meritocracy often make out Trump to be some kind of dunce who only got anywhere because his dad was rich. But if you examine the record, it’s clearly not true.

His recognition that he could get away with repeatedly stiffing contractors without becoming unable to do business going forward was genuinely insightful. The way he emerged from bankruptcy in Atlantic City by launching a publicly-traded company and then sticking his shareholders with his own personal debts was nothing short of brilliant. The problem with Trump is that he’s a bad person. He ran the federal government with the ethics of a private equity team taking over a nursing home.

There’s been this years-long thing where some liberals will say Trump made them miss George W. Bush, and others will say that’s insane, Bush was far worse, and way more people died as a result of Iraq than as a result of any bad Trump calls. And I certainly think it’s possible that McCain’s foreign policy views — which were more hawkish than Bush’s — would’ve done more damage in office than anything Trump ever did. But what people are pointing to with Trump is a complete collapse of public virtue.

The Bush family are aristocrats whose political ambition is tempered by a sense of noblesse oblige and concern for the dignity of the family name. McCain, always more popular and widely-admired than Bush, was part of a longstanding military family and had a demonstrated record of making personal sacrifices on behalf of doing the right thing. Trump and his kids are total scumbags. I’m really glad he didn’t make some of the foreign policy errors Bush did. But governance-by-scumbag is an alarming trend.

Good leadership isn’t meritocratic

Back when Barack Obama was in office, there was this right-wing cottage industry that was obsessed with trying to obtain Obama’s SAT scores in order to make some point about affirmative action. Mostly, they were seeking vengeance for liberals who’d spent years mocking Bush as a dim-witted beneficiary of legacy admissions.

But obviously what made Obama a much better president than Bush is that he subscribed to Democratic Party ideology, not that he could beat Bush at a multiple-choice reading comprehension test. I know some dumb Democrats and some smart Republicans. I hope that when Republican Party politicians are in office, they listen to the smart Republicans about things rather than the dumb ones. But I’d rather have a dumb Democrat win a Senate race over a smart Republican any day. Smarts just don’t matter that much.

In general, I think Obama did a good job. But he did make some serious errors, like underrating the amount of labor market slack still present in 2015-16. This was a very grave misjudgment that had truly harmful consequences. Unfortunately, plenty of smart people were involved in it. It would probably be dangerous to have seriously dumb people sitting in the Oval Office. But within the realm of reason, intellect isn’t going to be the difference-maker.

Joe Biden didn’t have a rich dad, benefit from legacy admissions, or benefit from affirmative action. He went to the University of Delaware, then Syracuse for law school, and he was in the bottom of his class at this not-super-prestigious law school. And while it’s obviously too soon to pronounce his presidency a huge success, it certainly seems to be off to a promising start. He has a good nose for public opinion, has hired a good team, seems to get along well with the relevant people, and excels at tapping into personal tragedy he’s experienced to connect with normal people despite having been in politics since the beginning of time.

And that’s just how it goes. The whole point of George Washington isn’t that he had penetrating insights into public policy — it’s that he provided character and ethical leadership under circumstances that lead a lot of countries to become military dictatorships. You don’t want people who are extremely stupid running everything. But in both government and the economy, it’s just not the case that putting the “best and brightest” in charge of everything is a good idea. And crucially, that’s not because the “best and brightest” secretly aren’t really the best and brightest. It’s because just assigning all power and responsibility and economic reward to the best and brightest is a genuinely bad idea.

Fair competitions produce unfair results

Back in 2019, Rafael Nadal earned $16 million in prize money playing tennis. Gael Monfils, in ninth place, earned $3 million.

These are the kind of sharp income disparities that lead Elizabeth Warren to say the economy is rigged. But of course pro tennis isn’t “rigged” in any normal sense. Fair, tournament-style competitions just tend to produce this kind of outcome where modest differences in ability lead to wild disparities in earnings. It’s honestly just more fun that way. We like to see high-stakes competitions, and we also like to see ability win out, and that’s what you get.

For the purposes of generating an entertaining spectacle, there’s nothing wrong with that. Indeed, there’s a reason why pro-inequality people almost always use examples that involve rich athletes or entertainers since it helps you get around questions of system-rigging.

But the basic reality is that it is not great for material resources to be distributed so unequally. The marginal dollar taken out of Nadal’s hands and given to someone in need will greatly increase human flourishing. There are lots of valid questions to ask about the macroeconomic impact of various kinds of taxes and the optimal design of welfare state programs. But the benefits of an egalitarian economic order are clear, real, and don’t fundamentally hinge on the idea that Nadal or anyone else did anything “unfair” to get where they are.

It takes hard work to be the champion, of course, but it’s equally obvious that the vast majority of people would never be as good as Nadal no matter how hard they tried. Almost everyone who’s successful works hard to get where they are. But they have also lucked into abilities that most people don’t have. And beyond that, they have meta-lucked into being alive at a time and place where the abilities they lucked into are valuable. Apparently, the highest-earning distance runner is just the one who happens to be American. An American can get better sneaker endorsements than a Kenyan or Ethiopian whose results are as good or better.

He’s great at what he does. He’s the beneficiary of dumb luck. It’s both, not either/or, and the sooner we accept that everything is like this, the saner we can be.

Round pegs and square holes

My read on a lot of what’s happening in elite cultural institutions in the United States is that we are currently living through a desperate scramble to make certain kinds of social justice goals and egalitarian commitments fit into a fundamentally unsound meritocratic framework.

What you need to do is actually change the framework — have a society that’s less based on sorting and ranking, and more based on equality.

In his meritocracy book, the Harvard political theorist Michael Sandel suggests that the most exclusive colleges should move away from tournament-style admissions. Instead, he’d like to see them set a minimum competency bar and then accept everyone who clears the threshold. That seems like a fine idea to me. What I’d like to see even more is for Michael Sandel to teach at a community college. Or for it to become stigmatized for rich people to donate money to already-rich universities. The really “in” thing to do could be to found new research centers in struggling communities, or to financially support educational institutions that serve low-income people.

In the political realm, I’d like to see less emphasis on taking the tech bros down a notch and more on just making the welfare state better, more generous, and more user-friendly.

But then, I would really like us to rethink Milton Friedman’s idea that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” and that everything to do with human welfare can be addressed through regulation. Friedman was a libertarian. He should know better than anyone how utopian it is to think that bureaucratic processes are going to successfully align everyone’s incentives.

I think he, the product of a more ethical period in American life, just underestimated the extent to which scams and shady dealings can be made to pay off. After all, it wouldn’t be hard to tell you a story about how changing up your nursing home management practices in a way that gets tons of your clients killed is going to be bad for business. And I could very easily tell you a story in which developing a reputation for not paying your contractors leads to your demise as a businessman.

The facts are pretty clear that poor ethics can frequently be rewarded. To have a healthier society, we need more emphasis on fair play, “an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay,” and creating an atmosphere in which people would be ashamed to tell their parents that their well-paid finance job involves identifying ways to make patient care worse. That’s not a simple switch we can flip. And while it obviously includes a regulatory component, it’s fundamentally not a regulatory issue. It’s a question of social values and getting away from celebrating tournament winners and being “the best,” and a shift to celebrating other kinds of virtues including humility, restraint, fairness, and a belief that some things just aren’t worth it.

And that, in turn, means trying to let go of petty jealousies and squabbling about whether So-And-So in Exalted Position X really deserves it. Nobody deserves to be as exalted as the most exalted people in America are right now.